Anesthesia best practices: Prepare, compare, be aware

Preanesthetic preparation also starts in the hospital with setup and function checks of anesthetic and monitoring equipment.

by Tamara Grubb, DVM, PhD, DACVAA

No one likes anesthetic complications. The goal of every anesthetist is to make anesthesia as safe as possible for each and every patient. Unfortunately, complications can occur during anesthesia, and when they do occur, there is often a rapid sequence of events that can put the patient in peril if not recognized and remedied quickly. Sometimes these complications are due to unforeseen patient responses to drugs or procedures, but, unfortunately, complications can also be due to human error (often as a result of inadequate training), lack of preparation, or omission of key steps in patient or equipment care. The most effective way to prevent complications is to establish anesthetic processes organized into checklists that ensure adequate preparation of the patient and equipment, minimize the chance for human error, and prevent omission of steps that could impact anesthetic safety. So, how do you incorporate all of this into the highest level of anesthesia care? Prepare, compare, be aware.

Prepare

As described in the 2020 AAHA Anesthesia and Monitoring Guidelines, the anesthesia period is not limited to the time that the patient is unconscious but is composed of four distinct but continuous phases: preanesthesia, induction, maintenance, and recovery. Patient needs for all four phases should be addressed before anesthesia is commenced to ensure patient safety. For example, preanesthetic preparation for the patient starts at home with the owner fasting the pet and perhaps administering medications like anxiolytics, antiemetics, and analgesics. Preanesthetic preparation also starts in the hospital with setup and function checks of anesthetic and monitoring equipment. This should be done first thing in the morning before any patient is anesthetized.

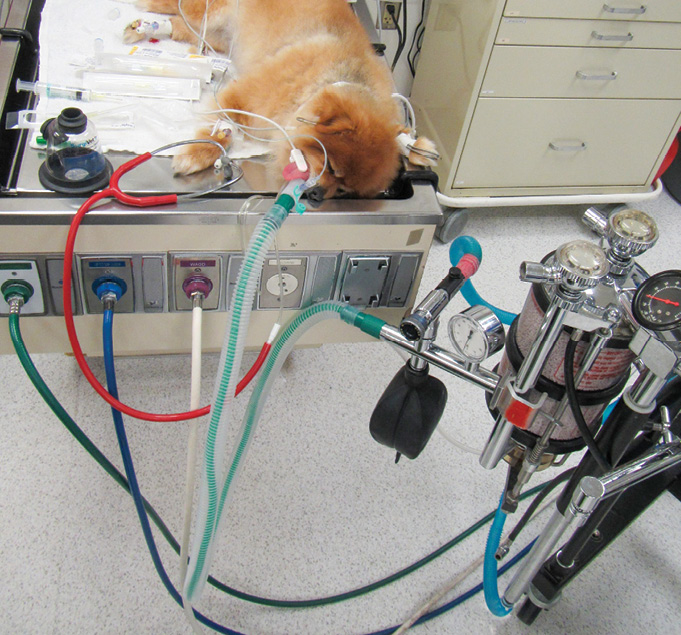

Certain tests (e.g., machine leak) should be checked between every patient. The criticality of a properly prepared anesthesia machine is often unrealized. But think on this: When the patient is intubated and connected to a breathing system that is connected to an anesthesia machine, that machine is part of the patient’s respiratory system. There is no way that the anesthetized patient can breathe without breathing through the machine components (Figure 1). Anything that goes wrong with the machine impacts the patient. So, when considering the importance of the anesthesia machine, give it the same importance as the patient’s respiratory system. Unfortunately, it is a part of the system with a lot of components and moving parts that can create respiratory complications. The anesthetic machine, along with the anesthetic monitoring equipment, must be prepared to function normally.

Figure 1

Compare

The best way to ensure optimal and thorough preparation is to have a checklist so that the anesthetist can compare their actions to the checklist actions. Checklists save lives by ensuring that nothing that the patient needs is missed. Maybe we think we get it all right all the time, but what about that asthmatic cat who didn’t get preoxygenated prior to induction since preoxygenation isn’t done for every patient in the hospital? Or the patient with cardiac disease who got 10 mL/kg (instead of 2–3 mL/kg) of intravenous fluids since 10 mL/kg is standard for the practice? As for the actual anesthetic drugs for each patient, standardized protocols are completely acceptable since the anesthetist will be familiar with patient responses to those drugs and can readily identify, and respond to, an unpredicted response.

But there are patients (i.e., those with moderate to severe comorbidities) who will need specialized protocols, and some patients receiving the standardized protocol will have specific needs. For instance, dexmedetomidine may be the sedative drug of choice for healthy patients in the hospital, but the dose is likely to change based on excitement level, age, and maybe even level of pain. The point is that, although standardized protocols are a good thing in general, every patient is still an individual and needs individual care.

The best way to see that patient as an individual is to be able to check off something similar to “Were the patient’s specific anesthesia requirements followed?” Drug protocol checklists should include anesthetic, analgesic, and support drugs (e.g., dopamine) for all four phases of anesthesia.

Figure 2

Comparing equipment setup and maintenance with checklists is likely even more important than using checklists for the patient since there is no standardized order for setting up and checking equipment. With the patient, the order of preparation naturally follows a flow: get the patient, get the drugs, medicate the patient. But there is no standard flow for equipment setup, and, unfortunately, steps are commonly missed. Anesthesia equipment can be “life supporting” if functioning normally or “life ending” if not functioning normally. That may seem like a rather dramatic statement, but it is a factual statement. Closed pop-off valve? Empty oxygen tank? Monitoring equipment not functioning? All of these are malfunctions that can lead to major complications or even death. Equipment checklists should be used for setup, to test proper function, and for daily/weekly/annual maintenance.

Here are four major checklist highlights:

1. Perform a leak check prior to anesthetizing each patient. A leak check only takes 30 seconds. Failure to perform a leak check can be dangerous for the patient (the patient may not be receiving adequate oxygen) and dangerous to humans (anesthetic gas could leak from the machine and be breathed in by personnel in proximity to the patient).

2. Never leave the pop-off valve closed. As recommended by the AAHA guidelines, a button-type pop-off is recommended (Figure 2). With a closed pop-off valve, the entire system—including the patient’s respiratory system—is rapidly pressurized and can lead to death within a matter of minutes.

Access the Resource Center

To improve awareness, ensure that employees are thoroughly trained using a training plan like the one at the AAHA Anesthesia Resource Center.

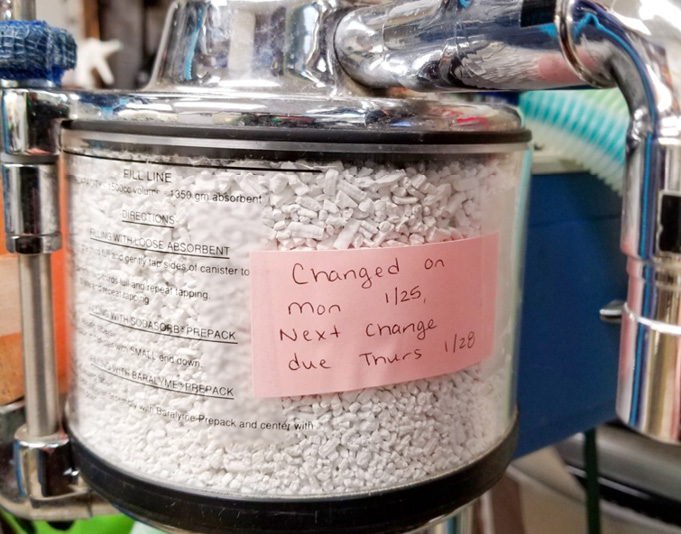

3. Ensure that the carbon dioxide absorbent in a rebreathing system is changed every six to eight hours of use by actually keeping track of use. Do not go strictly by absorbent granule color change—remember that purple granules can revert back to white and appear to be functional when they are not. The safest and most efficient way to remember is to have a visual count of the hours that the absorbent has been in use each day, or to write down a date that the absorbent is due for change. The former is preferred for machines that are used inconsistently. The latter is especially efficient if the machine is used roughly the same number of hours per day or week. Write that information on a piece of tape or paper that is on the absorbent canister so that everyone working with the machine is aware of when change is required (Figure 3). Failure to change the absorbent when it is no longer functional can lead to hypercarbia, and subsequent respiratory acidosis, in the patient.

4. Have your anesthesia machine and vaporizer checked/serviced according to the manufacturer’s recommendation, which is usually annually. A great way to remember the service due date, suggested by a practice consultant, is to schedule the machine’s “checkup” in the practice management software. If the hospital doesn’t currently have a machine maintenance technician, find one. Buy anesthesia equipment from manufacturers/vendors that specifically deal in equipment made for veterinary patients and ask them for advice. Local human hospitals may also have leads on who services anesthesia equipment in your area.

Figure 3

Be Aware

Numerous factors have been shown to contribute to anesthesia-related complications (depth of anesthesia, body temperature, etc.), and one factor contributes significantly to decreased complications: monitoring of physiologic variables. Not a surprise, just a good reminder on the importance of being aware of the physiologic status of the patient. Awareness of adverse effects of anesthetic drugs will improve the technician’s ability to effectively monitor and support the patient.

All anesthetic drugs obviously cause central nervous system depression, which can lead to depression of other organ systems, like the cardiovascular and respiratory systems. Most anesthetic drugs also cause direct cardiovascular and respiratory system depression. Depression of the physiologic function of these systems can lead to complications or even death. Thus, monitoring physiologic parameters is a requirement of care in anesthetized patients. In addition to monitoring, physiologic support, like oxygen delivery and maintenance of normothermia, is critical.

A detailed discussion of monitoring and support is provided in the 2020 AAHA Anesthesia and Monitoring Guidelines. Even with effective monitoring and support, anesthetic complications can happen and can rapidly worsen if not corrected. Protocols should be in place for rapid recognition and remedy of the problem. One of the most efficient ways to rapidly remedy complications is to have easily accessible complication-specific treatment algorithms for the anesthetist to follow. Algorithms for the most common complications are available in the AAFP Anesthesia Guidelines and can be used for dogs or cats. Of course, patient-specific responses must be considered, but the algorithms can help the anesthetist respond rapidly and prevent the situation from worsening.

To ensure that anesthesia is as safe as possible for each and every patient, remember to prepare (both patient and equipment), compare (use checklists), and be aware (monitor physiologic variables).

Online Bonus Content

|

Tamara Grubb, DVM, PhD, is a board-certified anesthesiologist (DACVAA) with a strong focus in pain management. Grubb owns an anesthesia and pain management consulting and continuing education business, which serves both small- and large-animal practices. She is a national and international educator and lecturer, a certified acupuncturist, and an adjunct professor of veterinary anesthesia and analgesia at Washington State University. Grubb serves on the board of directors for the International Veterinary Academy of Pain Management and was cochair of the 2020 AAHA Anesthesia and Monitoring Guidelines for Dogs and Cats. |

Photo credits: ©AAHA/Robin Taylor, photos courtesy of Tamara Grubb